In my second year of teaching, I had the opportunity to mentor a group of fifth-grade students as part of the IB Primary Years Programme (PYP) Exhibition. The PYP Exhibition is a culminating project that represents a significant milestone, where students synthesize their learning and take action on an issue that matters to them.

My students had chosen a powerful and timely topic: water quality. They were deeply curious about the impact of pollution on communities and the environment, especially in their own backyard, where São Paulo’s largest river, the Tietê, winds through the city. Once celebrated for recreation, the Tietê is now infamous for pollution. In 2010, National Geographic named it the most polluted river in Brazil.

Wanting to support their inquiry in a meaningful, real-world way, I thought I had found the perfect opportunity. A well-respected college professor was scheduled to give a public lecture on the topic that weekend. It felt like the stars were aligning. I reached out, shared that I’d be bringing a few of my students, and asked if he’d be willing to speak with them briefly afterward. He agreed. I was thrilled. This felt like one of those big “aha” moments in the making—an experience they’d remember.

But when the day came, I realized that most of what he said went over my students’ heads. And after the talk, when we approached him ... the air quickly shifted. He seemed surprised, even dismayed, to see fifth graders. I realized in that moment that although I had told him I’d be bringing students, I hadn’t clearly communicated that they were elementary school students. He exchanged a few brief words with us, then quickly dismissed the group.

My heart sank.

As a teacher, I felt I had failed them. My students had been excited, curious, and ready with questions, and yet they were met with disregard. It was a formative moment for me, and it changed how I approached expert and community partnerships in future projects.

In Project Based Learning, community partners and experts often play an important role in a project. When done right, these interactions can deepen inquiry, spark new perspectives, and show students how their learning connects to the world beyond the classroom. Not every expert is ready—or equipped—to engage with young learners. That experience taught me that meaningful partnerships require preparation on both sides.

Since then, I’ve carried a few important lessons with me, practices I began during my time in the classroom, and still advocate for any time an expert is involved in a project:

- Start local.

Some of the most powerful experts are already within your school community, such as parents, staff, teachers, and neighbors with lived experience. Don’t overlook the richness in your immediate surroundings. These individuals are not only knowledgeable but also deeply invested in the success of your students and the well-being of your school. Their insights often come with a level of care, context, and connection that outside experts may not always bring.

- Schedule a quick Zoom or phone call first.

Before they meet with students, have a conversation with the expert. Share who your students are, what they’re exploring, and how the interaction might unfold. Not every expert knows how to tailor their message for younger audiences—and that’s okay. But it’s far better to find that out beforehand than in front of your students. I’ve found that in some cases, a recorded video from the expert worked even better than a live Zoom or in-person meeting—it gave them time to prepare a thoughtful, age-appropriate message that aligned with the students’ inquiry.

- Frame the purpose.

Let your students know who the expert is, why they were invited, and what kind of insights they might offer. This helps students come prepared with a clear context and intention. Likewise, help your guest understand that their role isn’t to lecture, but to connect, listen, and respond. Framing the experience as a dialogue—not a presentation—sets the tone for meaningful exchange. Sharing a bit about the PBL method helps them understand the role of student agency in a PBL classroom. Depending on the project’s phase, the role of an expert will vary. Early on, during a project launch, reviewing the students’ Need to Know questions can help guide the conversation and ground it in authentic inquiry. Closer to the conclusion, when students receive feedback on their public product, equipping experts with a structured tool, such as the Ladder of Feedback Protocol, can help them provide meaningful and actionable input.

- Make it reciprocal.

Students are not just passive recipients of information. Position them as capable contributors. Encourage them to share their thinking and to ask bold questions. When experts view students as equals in conversation, deep connections happen. To support this, introduce protocols that help students generate meaningful questions before meeting with the expert, such as Project Zero’s Creative Questions routine or the Question Formulation Technique (QFT) from the Right Question Institute. These approaches help students move beyond surface-level questions to engage experts with curiosity, clarity, and confidence.

A Beginning-of-Year Strategy That Changed Everything

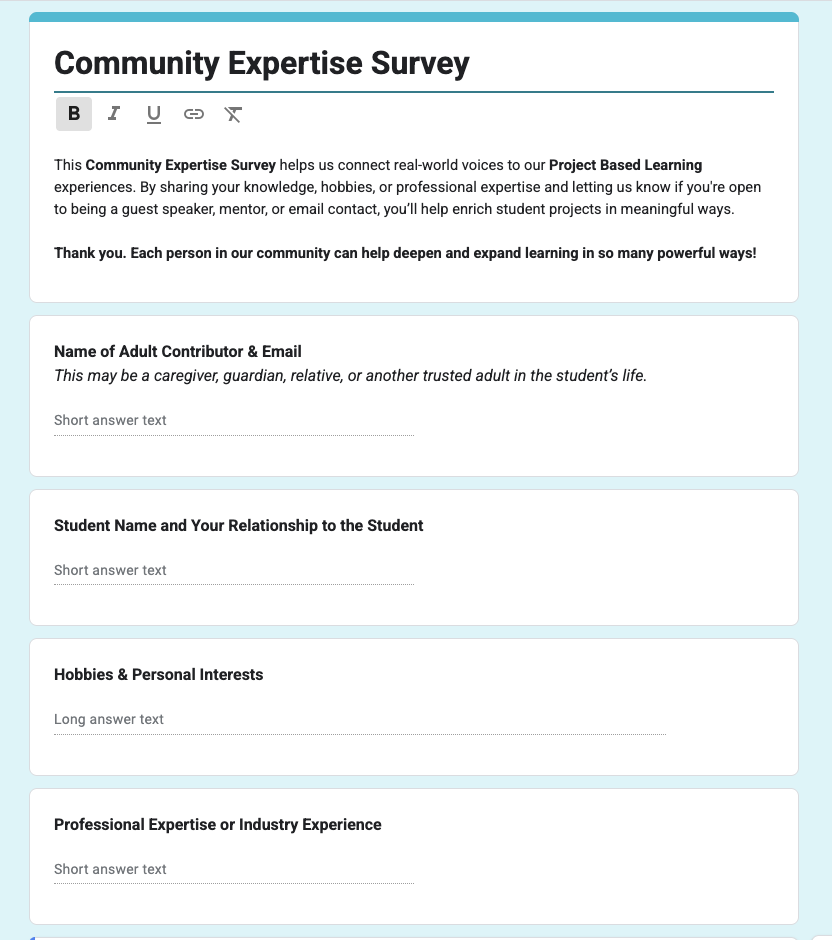

One practical approach I used with great success is a Community Expertise Survey. At the start of the year, I send an email with a simple form (a shared spreadsheet/digital survey) inviting families to share their areas of knowledge, hobbies, and professional expertise. I also ask whether they’d be willing to participate in a student project—as a guest speaker, mentor, or even just someone students could email with questions.

This strategy does more than build a bank of potential experts—it surfaces the unique passions and deep knowledge that community members hold, even beyond their professions. Families and the wider community feel seen. Students watch the web of learning stretch beyond the classroom. As the educator, I had a rich and relevant network to draw from as authentic projects began to take shape.

Some of the most memorable moments came when students saw someone close to them—like a caregiver, neighbor, or teacher—invited in as an expert. There’s a special kind of joy in seeing a student light up when a familiar adult is featured in a project, or when they discover something new about a teacher through their unexpected hobby.

I’ll never forget a Pollinator Garden Design project. We discovered that one of our teachers was passionate about native gardening and had cultivated a thriving pollinator-friendly garden—something few knew about. At the same time, a student shared that he kept bees with his family and proudly offered his experience as a young beekeeper. That day, he became an expert.

Don’t Overlook What’s Right in Front of You

We often hear about the challenges and time-intensive nature of collaborating with outside experts, but it doesn’t have to be that way. Through trial and error, I learned that with a few intentional practices, these partnerships can become one of the most rewarding aspects of a project.

The next time you begin planning an expert visit, I invite you to take a closer look at your community. Try one or two of these strategies. By doing so, you’ll help ensure that the kind of experience I shared earlier, where students were dismissed or overlooked, won’t happen. The opposite will be true: your students will feel seen, valued, and honored. I’ve even had the opportunity to hear students walk away so inspired that they’ve said, “I want to be like them when I grow up!”