As a teacher of literacy, I remember assigning my students informational reading and writing, and they just weren’t excited about it. It wasn’t as enticing as the mystery books, realistic stories, fantasy, or science fiction stories they had in their desks or the creative writing drafts they had in their writers’ notebooks. One third grader in particular, Madeline, asked me one day,

“Mrs. Lee, what does it matter if I read this informational text and write about it? It’s only for a grade. Who’s going to read it anyways? Who cares?”

Madeline’s question, and many similar experiences after, shifted my thinking and, without me realizing it, began my PBL journey. I asked myself, “Why are they reading this text? What will it help them accomplish? How can I help my students care?” Madeline, like all my students, needed to know that their learning was relevant and had purpose, beyond the teacher, the test, or the grade.

Informational reading: Did you know?

In 2000, Dr. Nell Duke published a study, 3.6 Minutes Per Day: The Scarcity of Informational Texts in First Grade, which documented that despite the “information age” in our culture, a mere 3.6 minutes of instructional time was dedicated to informational reading or writing in first grade classrooms. In low socioeconomic schools, instructional time was just 1.4 minutes. In the decade following, especially with the Common Core State Standards (CCSS) and the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) expecting a large portion of elementary students to be reading and writing informational text, there has been an increase of informational texts available in the classrooms. Unfortunately, many educators in their pre-service years didn’t have courses specific to teaching this genre, and professional learning on this topic is slow moving and inconsistent across the country.

In The Case for Informational Text, Dr. Duke describes four strategies that can help teachers improve K–3 students' comprehension of informational text (which really could apply to any grade level). Teachers should:

- Increase students' access to informational text.

- Increase the time students spend working with informational text in instructional activities.

- Explicitly teach comprehension strategies.

- Create opportunities for students to use informational text for authentic purposes.

The latter strategy is a perfect fit for Project Based Learning. The other strategies should be intentionally embedded in the lesson design to further strengthen the project by aligning to standards and scaffolding learning.

Taking a Deeper Look Inside Information

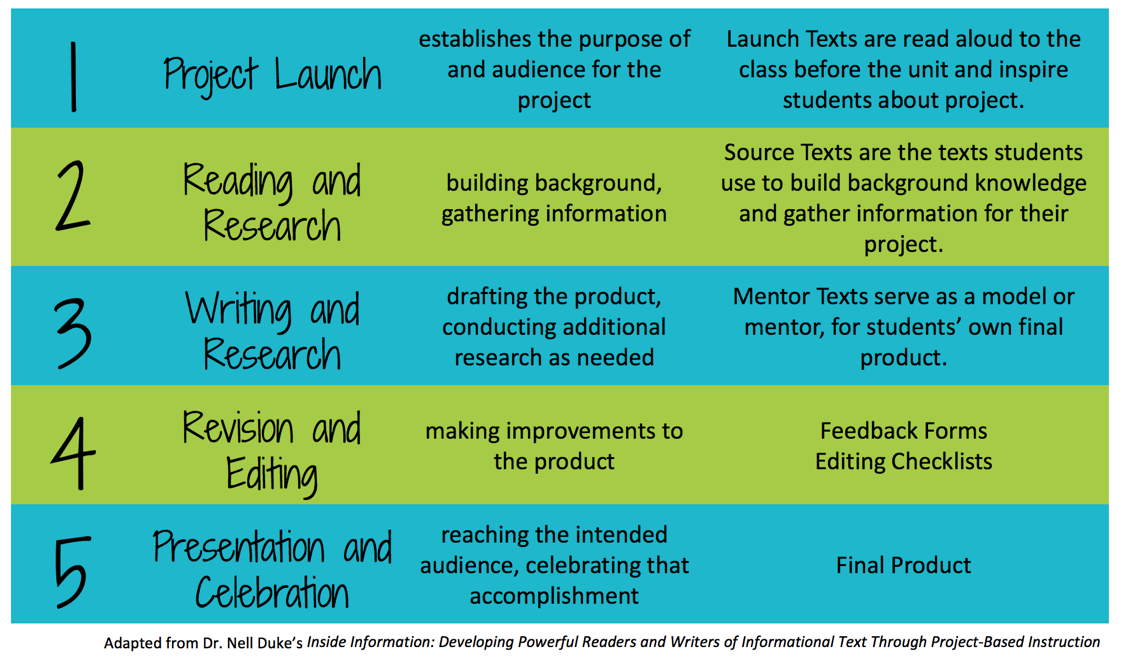

Two years ago, I facilitated a book study on Inside Information: Developing Powerful Readers and Writers of Informational Text Through Project-Based Instruction by Dr. Nell Duke in two schools. We had forty teachers involved in this study, half of whom had experienced in-depth PBL professional learning with me and were very familiar with the PBLWorks model of Project Based Learning, and half of whom had never tried PBL and saw this study as an entry point to learning. In Inside Information, Nell Duke explains the different phases of Project Based Instruction with informational text.

Regardless of where they were in their PBL journey, the teachers shared experiences and inquiries which prompted us to take a step back and evaluate how we taught literacy within Project Based Learning units. Our discussions pushed us to ask our own set of “Need to Know” questions so that we might become better teachers of literacy in PBL:

- Were we immersing our students in appropriate texts and using evidence-based instructional practices?

- In our unit designs, were we intentional about the audience and the authenticity?

- Did students have a purpose to their reading and writing? How could we integrate the topics in science, social studies, or other content areas to be effective in our use of time and instruction?

- What strategies could we teach our students to help them grow in their understanding of the informational genres?

In my post PBL and Literacy: A Perfect Match for Elementary Schools, I briefly addressed text selection, evidence-based instructional practices, and pairing standards from different content areas with literacy standards. Teachers still wonder, though, how might literacy look in the flow of a project?

Embedding Informational Text Literacy in All 4 Phases of a Project

For my more experienced PBL teachers in the study, they wanted to know how they could marry the PBLWorks project design with what they learned in the study. To that end, we asked the above questions as we redesigned our units to be more literacy focused. Our teachers found that their PBL units still had the 7 Elements of Project Design, but based on what we learned in our Inside Information book study, the teachers made these changes in how they reframed literacy in their project based units:

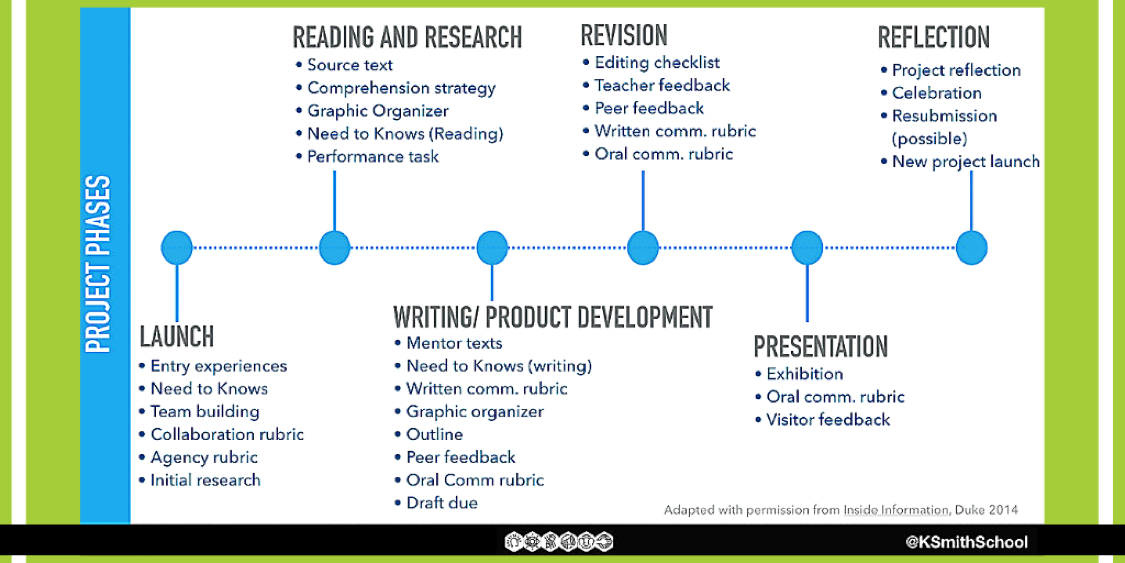

- Launch: Along with other entry event experiences, provide text that will spark questions and help students be curious about the topic and project. This could be in a read aloud from a book, an authentic text such as a newspaper article, a web page, or other media to highlight that informational text is part of their world. In addition to the “Need to Knows” for the project, what do students need to know about reading and writing in that genre?

- Building their Knowledge: Provide source texts in all forms (written, visual, and oral) to increase students’ access to informational text. Teach and assess text comprehension strategy/strategies to help students make sense and understand this new information.

- Develop and Critique:Remember to engage students with mentor texts of the type of writing you expect from them as writers. Provide opportunities for multiple drafts and feedback specific to the genre. Use communication rubrics as feedback for the oral presentations. Leverage one-to-one or small group conferencing to focus on the writing and the status of the project. Allow students time to revise the writing and choose how it’s presented (with technology, a play, a debate, or product).

- Presentation: Encourage written and oral visitor feedback.

Katherine Smith Elementary captured this literacy approach to project based instruction and the essentials of PBL in their graphic below. Two areas that caught my attention in their adaptation of Dr. Nell Duke’s project phases were “Need to Knows” specific to reading and writing and the addition of a project reflection. Both are hallmarks of the PBLWorks model.

Project Based Literacy with Purpose

Unlike my former student, Madeline, who wondered about the purpose of her informational reading and writing assignment, the kindergarten students in Ms. Lessway’s class this April will be able to articulate their purpose:

“We’re working with the zoologists to help visitors to the zoo learn about the animals at our local zoo.”

Last year, the diverse population in Ms. Vanlinthout’s and Ms. Farmer’s class of English Learners knew that they were making informational video presentations to help new families learn more about their school culture and the people in it. Recently, the second graders in Ms.Griesinger’s class proudly created presentations to inform their principal of an inequitable situation in their grade level and persuade her to make a change. These examples show that informational literacy instruction can be engaging and meaningful for students. When teachers utilize Project Based Learning, they create opportunities for students to use informational texts in authentic, purposeful ways.