What happens when we invite students to share the most personal parts of their lives through schoolwork? Can learning that centers their experiences also help them grow academically?

As a former first-grade English Language Development (ELD) teacher in southern San Diego, I discovered the transformative power of Project Based Learning (PBL) when I reimagined a language unit through the lens of student identity. I had seen PBL in action and was in awe of the meaningful work students and teachers did together. So I took a leap of faith and told myself, “Candice, just try it—one unit, 30 minutes a day.” Technically, I was still teaching the standards and used the mandated curriculum as a guide. With the support of Gold Standard PBL Design Elements and a commitment to collaboration, even the quietest students began to speak. PBL taught students they had a voice but how? And how can we combine academic rigor with opportunities for meaningful language development to uplift multilingual students? These are the questions I ask when writing project-based curriculum units for PBLWorks and are the questions I will answer today.

1. PBL Honors Student Voice and Identity

This first project—one I’ll share more about in a moment—taught me something essential: when students are invited to bring their full selves into the classroom, they don’t just participate—they thrive.

For many of my students at the time, living near the US-Mexico border meant that crossing between two nations was part of everyday life. This daily journey shaped how they saw themselves and the world. Chicana scholar Gloria Anzaldúa calls this space “Nepantla,” a Nahuatl word meaning “in-betweenness,” a fitting description of the cultural complexity my students navigated.

Most of my students were recent immigrants. Many were in the “silent period” of language acquisition, still adjusting to a new school system, culture, and language. While teaching the district’s ELD curriculum, I noticed it lacked connection to their lived realities. It felt uninspiring to me as a teacher, so how must my students feel?

When the Project Became Personal

The project I designed was called Crossing the Border With Our Five Senses. It explored “How can we use our five senses to show who we are through poetry?” It invited students to explore the experience of border crossing using sensory language. This wasn’t an abstract exercise. It was grounded in what students knew best: their own journeys.

When I launched the project, one student asked, “Mrs. A, can we talk about this?” That question became the project’s emotional core. I assured the class: Yes. This is a safe space. Your stories matter.

We co-created word banks, acted out scenarios, and learned to write sensory poems. As students explored what they saw, heard, and felt while crossing the border, they gained confidence in their language use. Collaboration and storytelling became our instructional foundation.

2. PBL Centers Collaboration—and With It, Language Development

In our border project, collaboration wasn’t an add-on: it was the heart of learning. Language acquisition isn’t just about memorizing vocabulary or drilling grammar rules. According to Stephen Krashen, a pioneer in second language acquisition theory, learners acquire language most effectively when they understand messages in meaningful, low-stress situations. While he emphasizes listening and reading (comprehensible input), he also recognizes that speaking in authentic conversations can support acquisition when it promotes understanding, feedback, and connection.

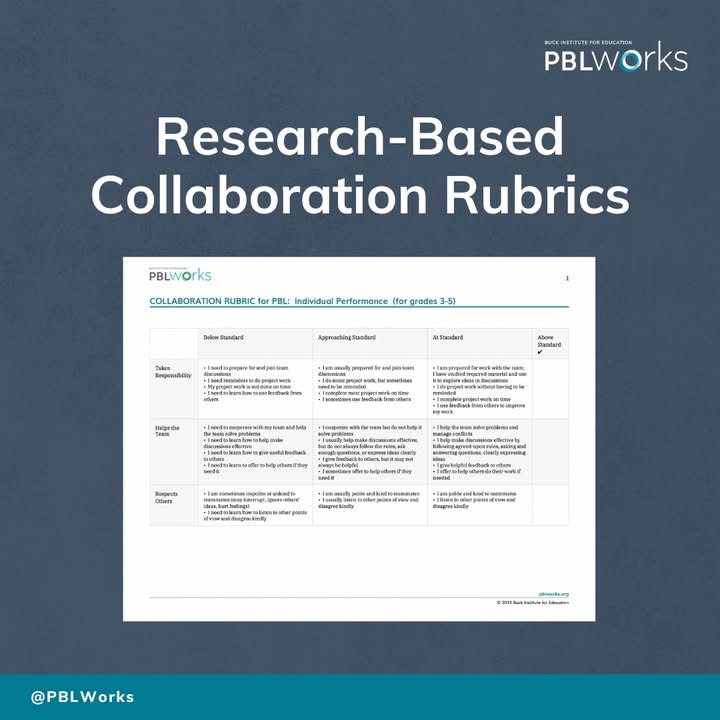

This aligns closely with PBLWorks’ definition of high-quality PBL, which emphasizes collaboration as a core design element. When students work together to solve problems, co-create products, and revise their work, they are using language with purpose. For multilingual learners, this type of social, task-based interaction is vital for growth.

This aligns closely with PBLWorks’ definition of high-quality PBL, which emphasizes collaboration as a core design element. When students work together to solve problems, co-create products, and revise their work, they are using language with purpose. For multilingual learners, this type of social, task-based interaction is vital for growth.

In our project, students brainstormed in pairs, gave each other feedback, and shared their poems in public readings. With each interaction, they practiced oral language, academic vocabulary, and confidence.

3. PBLWorks Curriculum Provides Built-in Scaffolds for MLLs

Today, I work with PBLWorks to develop a PBL curriculum that builds these same opportunities into every unit. Each project is designed around authentic inquiry and includes built-in scaffolds to support the linguistic and academic development of multilingual learners.

Some of the supports integrated into PBLWorks curriculum include:

- Sentence frames and modeling to support oral and written academic language

- Speaking and listening routines that provide structured opportunities for student talk

- Collaborative learning protocols that help all students participate meaningfully

- Culturally relevant entry points that allow students to connect their lived experiences to content

- Public products that give students a real purpose and audience for their work

These structures are especially powerful for multilingual learners because they make content accessible without reducing complexity. As researchers Aída Walqui and Leo van Lier explain, academic success for English learners depends on classrooms that are “interactive, contextualized, and cognitively engaging.”

PBLWorks’ TEACH curriculum embodies these principles by aligning content, language, and identity. It doesn’t ask teachers to choose between honoring student experience and teaching rigorous standards. It shows how both can be done together.

When my students shared their poems at the end of our border project, they stood a little taller. They weren’t just practicing English. They were reclaiming their voices. They knew they were seen.

That kind of learning sticks.

The success of the project came not from my instruction alone, but from sharing power with students inviting them to bring their full selves into the classroom. This aligns with one of PBLWorks’ core equity levers: leveraging student assets and identities as drivers of learning. By honoring their lived experiences, positioning them as knowledge-holders, and co-constructing the learning process, we shifted the power dynamic in the room. What emerged was a classroom culture rooted in trust, relevance, and collaboration, a space where learning felt joyful, rigorous, and healing.

Honoring Voice, Centering Stories

What is one small change you can make tomorrow to give students more opportunities to speak with purpose?

If there’s one thing I’ve learned, it’s this: multilingual learners do not need to be “caught up” before they can participate. They need to be engaged through relevant, rigorous, and language-rich instruction that values their experiences.

Project Based Learning, especially when built with intention like the curriculum at PBLWorks, offers a roadmap for doing exactly that. Our curriculum is intentionally designed to center students. Grounded in the belief that students don’t need to be “caught up” before they can participate, each unit engages learners through relevant, rigorous, and language-rich experiences that value their identities and lived experiences. Driving questions spark inquiry connected to real-world issues, while scaffolds support access to complex tasks without reducing cognitive demand. Rooted in PBLWorks’ equity levers, the curriculum creates space for collaboration, reflection, and authentic expression through meaningful products and public audiences. By honoring students’ cultural and linguistic assets, the curriculum positions all learners as active, capable contributors to their communities and the world.

If you are an educator working with multilingual learners, I invite you to reflect:

1. How can your curriculum better reflect the lived realities of your students?

2. How can collaboration become a daily structure for language practice, not an occasional activity?

3. What is one small change you can make tomorrow to give students more opportunities to speak with purpose?

Start with one project. Use students' stories as the entry point. Look to the PBLWorks curriculum and resources to guide you. And most importantly, trust that your students already have something powerful to say.

They’re just waiting for the space—and the audience—to say it.

Walqui & van Lier (2010), Scaffolding the Academic Success of Adolescent English Language Learners

Krashen (1982), Principles and Practice in Second Language Acquisition