Do you create team contracts for your PBL units only to find the contracts carry little influence over how the students in the team collaborate together? When I first began to design and facilitate PBL curriculum in my 9/10th-grade physical science classroom ten years ago, I struggled to create meaningful team contracts.

It wasn’t until I helped to develop the restorative justice program at my school that I found a way to create more meaningful group contracts that could be used throughout the project. I realized that I could use talking circles, a core restorative practice, to create team contracts. Since many group conflicts dealt with interpersonal communication and conflict management issues, incorporating a restorative practice approach to support team collaboration made sense.

In the context of restorative justice, the talking circle typically occurs after a behavioral incident and is used to heal the harm that has been inflicted in the community. In the context of PBL, the talking circle I used occurred prior to student team formation in a project and is used to emphasize the importance of collaboration, create the team contract, and provide strategies to help students navigate future conflicts that often arise during team collaboration. When used in this way, the talking circle takes a preventative approach to behavioral management and moves toward a restorative practice in my classroom.

Benefits of Incorporating Talking Circles to Build Team Contracts

I love using a talking circle about collaboration to create more meaningful team contracts because it:

- provides space and voice to students who often go unheard.

- allows student teams to establish collaboration goals important to them.

- helps students navigate team conflicts.

- helps to prevent negative outcomes during team conflicts.

- provides a common experience to reflect upon when conferencing with a team or mediating a conflict.

- develops the culture of collaboration in my PBL classroom.

Talking Circle Basics

Participants of the talking circle sit in chairs forming, yes, a circle around the “talking pieces” laid out in the center. The facilitator of the circle, commonly called the “Circle Keeper,” shares a prompt that participants respond to when the talking piece is passed to them. In order to promote equity of voice in the class, only the person with the talking piece is allowed to speak so that each person has space to share their thoughts without interruption. Participants in the circle have the option to pass the talking piece to the next person without sharing. It’s important to note that, in addition to the facilitator responsibilities, the Circle Keeper is also a participant in the circle.

Use of Talking Circles to Emphasize the Importance of Collaboration

I first used talking circles to emphasize the importance of collaboration and help develop group contracts during a project about music in my 9/10th-grade physical science class. To enhance the circle conversation, I invited 12th-grade students to the circle who had previously completed projects in my class and used team-built products from those projects as the talking pieces. It was amazing to see how the thoughts shared by my former students on the importance of collaboration carried more weight with my 9/10th-grade students than my voice alone could.

After the opening activity, creating the norms, and introducing the talking pieces, guests, and topic, the talking circle was organized into three main sections.

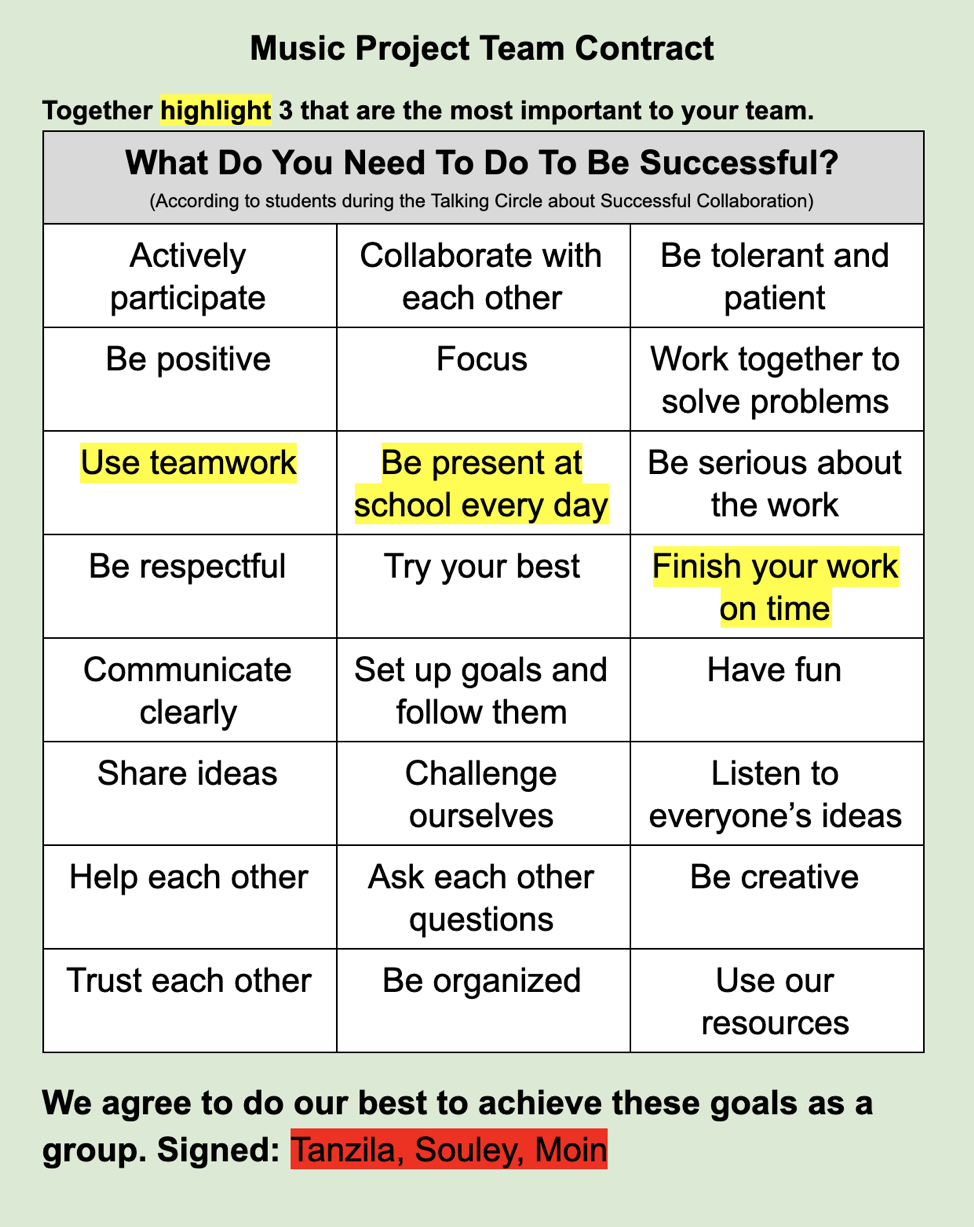

First, students wrote one word or phrase on an index card in response to the prompt: “What makes for successful collaboration?” After each student shared their word and passed the talking piece for the next person to share, they placed their index card in the middle of the circle.

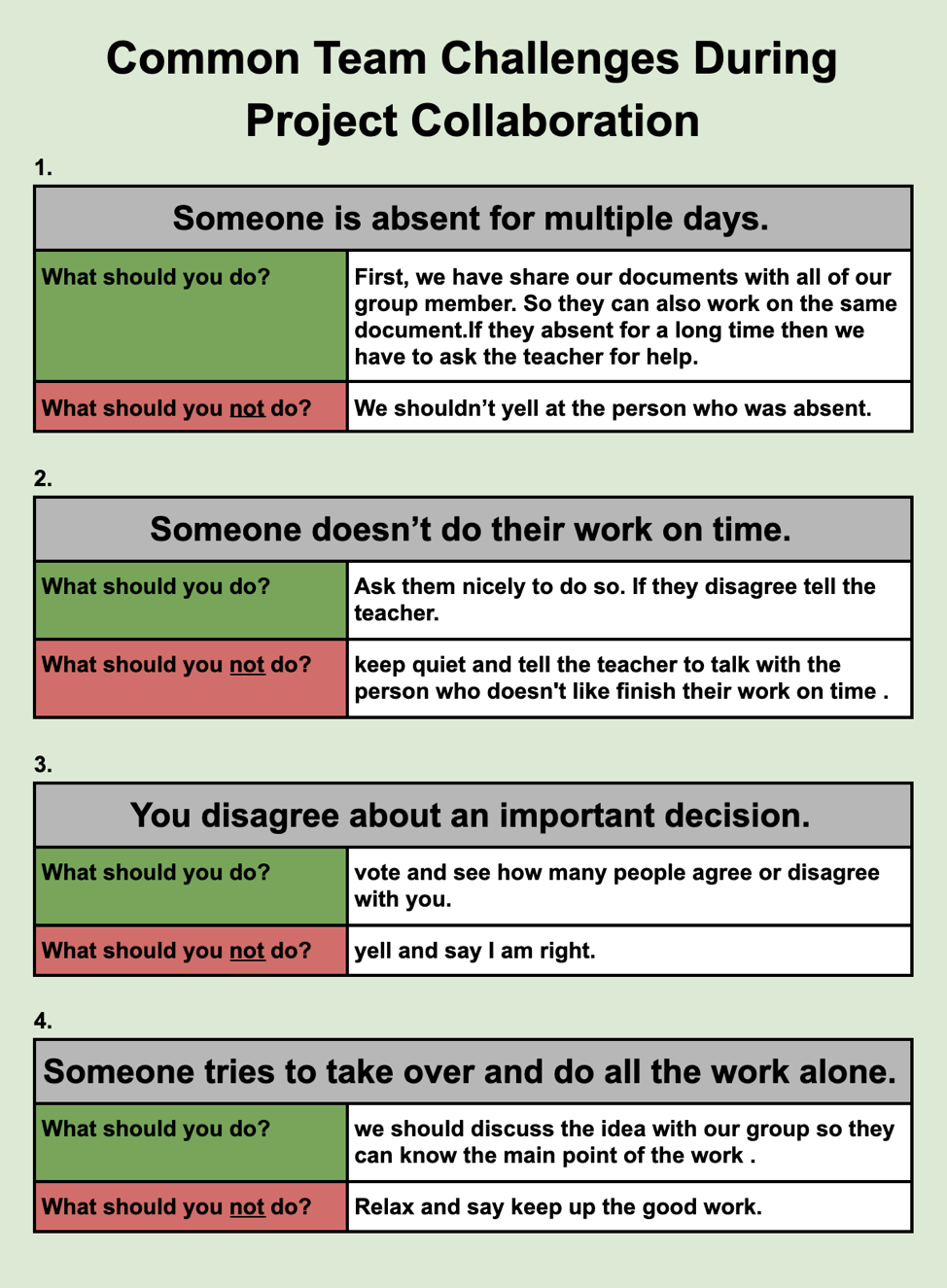

During the second section, students responded to the question, “What are common team challenges during project collaboration?” While students shared, I made a list of their examples on the board for all to see. Then, in groups of four, they selected one example scenario to create and perform a short “Don’t and Do Skit” that in one scene shows how to not handle the scenario and in the other scene shows how to correctly handle the scenario.

The third section had students popcorn out their response to the prompt, “Why is collaborating in groups important?” We then closed the circle with a brief celebration activity.

That afternoon, I took the collaboration words on the index cards and the conflict scenarios to create the team contract document.

Creating Team Contracts

The day after the talking circle, students formed their project team and worked together to establish their contract. The contract was split into three sections.

|

|

|

|

|

|

In addition to the contracts, I used the collaboration words on the index cards to create a Collaboration Bulletin Board. On the board, placed among the index cards, I posted each team selfie. The group contract and the bulletin board became really important resources for me and the students during the project.

Team Contract Use During the Project

Throughout the project, I was able to create reflection prompts based on team contracts. Additionally, the contracts were useful when I conferenced one-on-one with groups. When I did have to intervene during group conflicts, the contract and bulletin board were meaningful points of reference to help the group positively move forward.By incorporating student responses about collaboration from the talking circle into the team contract, I was able to make the impact the circle experience had on students endure as they worked together throughout the project.

First, teams selected three of the collaboration words generated from the circle they agreed to adhere to as they collaborated on the project.

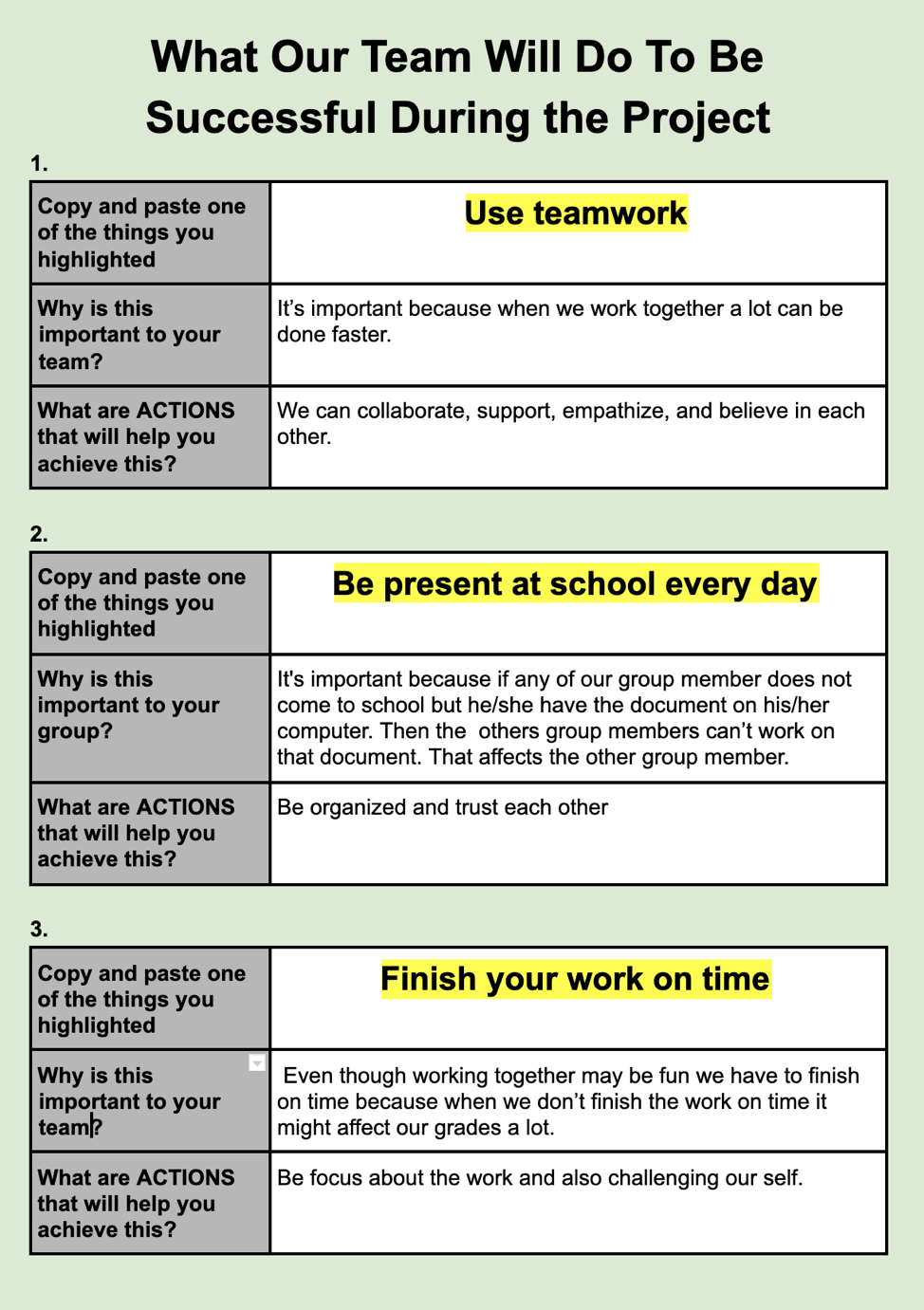

First, teams selected three of the collaboration words generated from the circle they agreed to adhere to as they collaborated on the project. Second, for each of these words, students worked together to explain why this word was important to their team, and what actions they would take to make sure they lived up to the word they selected.

Second, for each of these words, students worked together to explain why this word was important to their team, and what actions they would take to make sure they lived up to the word they selected. In the final section, student teams looked at four of the conflict scenarios the students shared during the circle and described how they should react and how they should not react. When teams completed the three parts of the contract, they signed their name and took a team selfie with my class camera.

In the final section, student teams looked at four of the conflict scenarios the students shared during the circle and described how they should react and how they should not react. When teams completed the three parts of the contract, they signed their name and took a team selfie with my class camera.