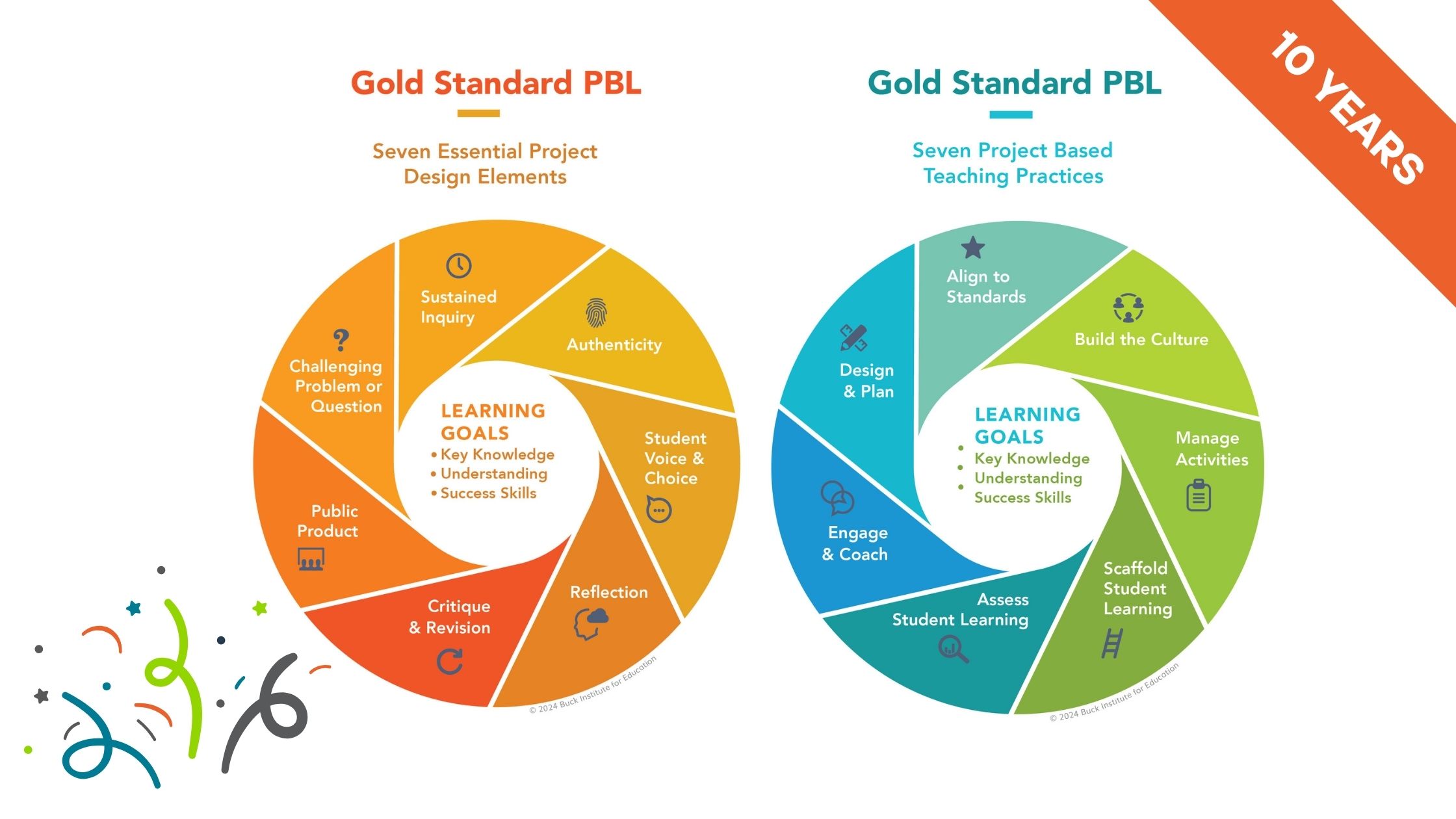

Time flies! It was in the fall of 2015 that we published Setting the Standard for Project Based Learning, in partnership with ASCD. In the book, which became a bestseller for ASCD, we laid out our model for Gold Standard PBL. Its 7 Essential Project Design Elements and 7 Project Based Teaching Practices have become the touchstone for all of our work since then—and the work of many other educators too. The book has sold over 100,000 copies (pretty good for an “education book”), and it is often cited by researchers and practitioners.

Time flies! It was in the fall of 2015 that we published Setting the Standard for Project Based Learning, in partnership with ASCD. In the book, which became a bestseller for ASCD, we laid out our model for Gold Standard PBL. Its 7 Essential Project Design Elements and 7 Project Based Teaching Practices have become the touchstone for all of our work since then—and the work of many other educators too. The book has sold over 100,000 copies (pretty good for an “education book”), and it is often cited by researchers and practitioners.

At the time, our model for Gold Standard PBL represented our best thinking about how to make sure the projects teachers designed and implemented were high quality. There were many different definitions of and approaches to PBL, and some of them were a little “sus” as they say today. This situation is still true to some extent—"dessert" projects, fun but lightweight, can be easily found in an online search—but I think our model helped make PBL a more rigorous teaching method and gain wider acceptance today.

Roots of the Model

We did not come up with the Essential Project Design Elements out of nowhere—they were rooted in the history of the Buck Institute for Education. In 1998, it published the booklet An Overview of Project Based Learning by Dr. John W. Thomas, which is still cited in the research literature. After observing PBL in practice at several Bay Area high schools, Thomas described four “common features of PBL”: content, conditions, activities, and results. The following year, he, John Mergendoller, and Andrew Michaelson wrote Project Based Learning Handbook: for Middle and High School Teachers (updated second edition by Thom Markham in 2003). It identified six familiar-sounding “defining features of PBL”:

- The Project is the Curriculum

- Student Responsibility

- Real Work

- Contextualized Learning

- Frequent Opportunities for Feedback

- Impact on "Like Skills"

Fast forward to 2010 (still with me?), when John Mergendoller and I wrote an article for ASCD’s Educational Leadership magazine, “Seven Essentials for Project Based Learning,” which is still available on their website. It included:

- A Need to Know A Driving Question

- Student Voice and Choice

- 21st Century Skills

- Inquiry and Innovation

- Feedback and Revision

- A Publicly Presented Product

As you can see, these “essentials” are pretty close to the Gold Standard PBL model, though we made some refinements—and made the tough call to drop “Need to Know.” We decided it was more like an argument for PBL itself, the reason it works, not something a teacher designs into a project per se. A fine point, maybe—some people I know still miss it. And one thing we added to our model around 2012, which still appears in the center of our graphics of Gold Standard PBL, was—lest we forget the whole point—the Learning Goals: Key Knowledge, Understanding, and Success Skills (our term for “21st-century skills").

For our 2015 book, we decided to add the Seven Project Based Teaching Practices to emphasize the crucial role of the teacher in making PBL work effectively. We also wanted to show teachers that they already had some of the skills and qualities needed in a project-based environment; they did not need to totally reinvent their teaching.

Reflections on the Model Today

The Gold Standard PBL model was not carved in stone. I, the staff at PBL Works, and our National Faculty (the folks who bring the model to educators in our workshops and see their reactions) are dedicated to ensuring PBL is high quality, and over the years our thinking about the Essential Elements evolves. We consider their importance, new aspects, and sometimes even wonder whether they're still the right ones. I recently asked our staff and NF for their reflections on the Essential Elements (thanks all!), and here’s what they told me, along with a few of my own thoughts:

Challenging Problem or Question

John Larmer:

We decided to add “Challenging Problem” to allow for projects that were focused on a “design challenge” or “problem statement” rather than an exploration of a question. But this is a bit academic sounding, so I sometimes wonder if going back to just “Driving Question” might be a good idea. The projects we design for the curriculum units in our TEACH app and coach teachers to design in our workshops all feature a DQ.

Randi Downs, National Faculty:

When I coach teachers around this, I always ask, “What do people in the world DO with this content?” Also, “What will students learn, do, create?” This allows for deep discussion around the DQ.

Sustained Inquiry

John Larmer:

This is the element that is often the most challenging for educators; it represents a big shift from the traditional paradigm of education, the didactic approach. It has more profound implications for classroom practice than other elements, such as using a driving question or allowing students to have more choices.

Honor Moorman, National Faculty:

I used to feel a bit of tension between the ideal of having students drive the inquiry through their need to know questions versus the fact that I had already mapped out all the milestones of the project based on anticipated need-to-know questions that were aligned to the content. Inspired by this Volkswagen Darth Vader Commercial, my thinking shifted when I gave myself permission to facilitate my projects with “sleight of hand” when necessary, making sure I guided students’ learning experiences in such a way that would effectively lead them to ask the key questions I had planned on. Of course, my students often arrived at those anticipated need-to-know questions on their own, without any prompting—and that was pure magic!

Authenticity

John Larmer:

I said this a long time ago, but I still think there’s a scale of authenticity, from “fully” to “somewhat” authentic. The former include projects that directly address issues in students’ lives, communities, and the “real world” (which includes the real world of school, for young people). The latter includes simulations, which I know PBL purists look down on, but… Sometimes a simulation of a real-world situation makes for a good project (this is especially true for history, I’ve found).

Taya Tselolikhina, PBLWorks Staff:

Authenticity has never been more essential than it is today, especially with the proliferation of generative AI. This is our opportunity to give students access to apply their learning in a way that is preparing them for their future.

Randi Downs, National Faculty:

When we talk about authenticity, I find it to be an opportune time to discuss personal relevance and community impact. Why does this matter to the students, the community, the world? It’s a great time to bring out Project Zero’s “The 3 Why’s” thinking routine, which can be used with both teachers and students throughout the project.

Student Voice & Choice

John Larmer:

Back in 2015 and before, these two ideas sounded good together, but “voice” was often overlooked. In recent years we have tried to differentiate them, as voice involves allowing students to express themselves authentically, which is clearly different from asking them to choose, say, a product or teammate.

Erin Gannon, National Faculty:

Emphasizing student voice and choice is such an important way to engage students in the post-Covid classroom, where they can often feel a disconnect with the standards we are focused on learning. When we can offer them opportunities to have a say in what questions we are investigating and how they share their knowledge, they can find greater relevance in the content, and their interest is piqued. Students don’t want learning to be imposed on them, they want to dig into topics that matter to them and to be able to express themselves as they create products.

Honor Moorman, National Faculty:

The paradox of choice is that while some degree of choice has benefits, too much choice can be overwhelming and dissatisfying. When trying to decide how to incorporate student choice into my project design, I used to overthink all the options which led to analysis paralysis.

My breakthrough was inspired by Carol Ann Tomlinson’s framework for differentiation, in which she articulates the key areas of content, process, and product. Now, when I’m planning a project, I organize my thinking around the element of student choice into those same three categories: How might students have choice over the content? the process? and/or the product?

Realizing that more choice is not necessarily better than some choice, I try to limit students’ choice overload too by presenting them with a short list of options or having them brainstorm just a few choices before selecting one. See our Strategy Guide on Facilitating Student Choice for details.

Reflection

John Larmer:

Just noting (for the record) a common misquotation: John Dewey, the grandfather of PBL, never said, “We do not learn from experience, we learn from reflecting on experience”—although he would have agreed with the idea! He did write extensively about the value of reflection in the learning process, but not quite succinctly. (And btw, he definitely would not have written, “If we teach today’s students as we taught yesterday’s, we rob them of tomorrow” despite what it says on Goodreads, Reddit, Quora, etc.!)

Lindsay Teeples-Mitchell, National Faculty:

I don't think reflection has ever been more important than it is today. In a time when students face rapid change, social pressures, and information overload, meaningfully embedding reflection into the day-to-day of a project gives them space to pause, process, and find meaning. It also allows us to humanize our learning together and connect it to something authentic, often related to identity, values, and/or community impact. Reflective dialogue (through peer feedback, group check-ins or public presentations) also helps them practice the skill of listening and builds a culture of trust, iteration, and shared responsibility—all of which could not be more important in our current climate.

Critique & Revision

John Larmer:

We used to say “feedback” but critique has a more two-way connotation; we talk about a “culture of critique” in a PBL classroom. And revision has always been important to link to feedback, to remind us of the iterative nature of product development and the importance of doing high-quality work.

Maggie McHugh, National Faculty:

Early in my career, I thought about critique and revision so differently than I do now. Back then, critique was something that came only from me, the teacher. Revision was an independent task, guided by a checklist and done mostly in isolation. And honestly, both happened at the end of a unit, almost as a formality before the final turn-in. Then came PBL—and everything shifted.

Now, critique and revision are woven into the very fabric of my classroom. They’re not separate steps at the end; they’re part of the journey from the very start. With a growth mindset leading the way, my students and I lean into feedback together—celebrating what’s working, questioning what could be stronger, and knowing that every product, every idea, can always be improved. This change has made my classroom vibrant, collaborative, and alive with learning.

Honor Moorman, National Faculty:

As an English Languages Arts teacher, I often spent my weekends buried under stacks of student writing that needed my feedback. Over time, the act of commenting on student work began to feel like a huge burden. But as I began to focus more on providing opportunities for students to engage in peer critique, I developed the mantra: “Feedback is a gift, so give generously and receive graciously.” One day, I heard myself saying this to my class, and I took it to heart. From then on, when faced with a mountain of student papers, I take a deep breath, say my mantra, and embrace the process. And the more I incorporate self-assessment and peer critique into my practice, the more students embrace—and apply—the gift of my feedback, too.

Public Product

John Larmer:

Another way we like to say this is “making student work public”—because it doesn’t just mean “making a presentation” which many people might think every project requires as a culminating event. Students can make their work public at several stages of a project, getting feedback on initial ideas, rough drafts and prototypes, and final products from peers, experts, or end-users of a product. The bottom line remains the same: a public product is not one that is simply shared with classmates and the teacher, like the same-old, same-old oral presentations and bulletin board displays. Sharing it beyond the classroom ups the realism and the stakes, and hence the quality.

Brian Schoch, National Faculty:

Teachers often ask me if they have to do a public product or involve a public audience. I often respond by saying, “You don’t have to, you get to.” I know it’s a cheesy answer, but I also know how much the involvement of a public audience can completely change the motivation from the students and the impact of a project. I’m reminded of times as a teacher when a project came to life because the audience was going to be different from the typical “presentation to the class and teacher.”

When I’ve involved a public audience, I’ve encountered much better engagement and outcomes from my students and have seen students’ mindsets shift from trying to “collect points” to producing high-quality and thoughtful work.

The Gold Standard Lives On

I’ll end with a shout-out to my co-authors of Setting the Standard, Dr. John Mergendoller and Suzie Boss. John was the Buck Institute for Education’s executive director at the time, and his academic background (and editing chops) greatly enhanced the book and grounded our model in research. Suzie was a long-time member of our National Faculty, and her experience as a journalist and author of many of her own books brought insightful storytelling to the chapters she wrote, along with detailed examples of projects in action. She went on to write Project Based Teaching: How to Create Rigorous and Engaging Learning Experiences, which we co-published with ASCD in 2018 and is still in print. She fleshed out the Seven Project Based Teaching Practices with stories gathered from practicing PBL teachers, and it too became an ASCD best seller.

The Gold Standard PBL model has helped teachers, instructional coaches, and education leaders advance their understanding and practice of Project Based Learning. We hope it continues to do so as the movement toward more engaging, inquiry-based, real-world relevant learning continues to grow. Students today need it more than ever!