In the PBL classroom, we frequently need to transition students from learning something new to applying that learning in project work time.

One effective approach is to work with students as apprentices.

My husband, Charles, is a ceramics artist who sometimes teaches classes in his studio. Picture this: potters’ wheels and large work tables fill the space; clay, glazes, and various tools line the shelves on two sides of the room. In one corner, Charles sits at his wheel demonstrating how to put a handle on a coffee mug as the students gather around watching. His brief lesson over, he sends everyone off to continue working on their projects, encouraging them to call him over if they need help with their handles.

As the students work, Charles moves from person to person, observing and stepping in to coach whenever he sees an opportunity. Sometimes this is just a verbal nudge, “Try bracing your elbow against your knee to keep it steady.” Other times, he may ask, “Can I show you something?” before guiding the students’ hands or shaping their clay. At other times, he may simply inquire, “How’s it going?” encouraging students to identify aspects of their work they’d like help with.

At the end of the class, Charles gathers the students together again, and invites one or two of them to highlight something important they’ve discovered, or asks everyone to share a few words about what they’ve accomplished during work time.

This is an illustration of the apprenticeship model. In schools we call it the workshop model.

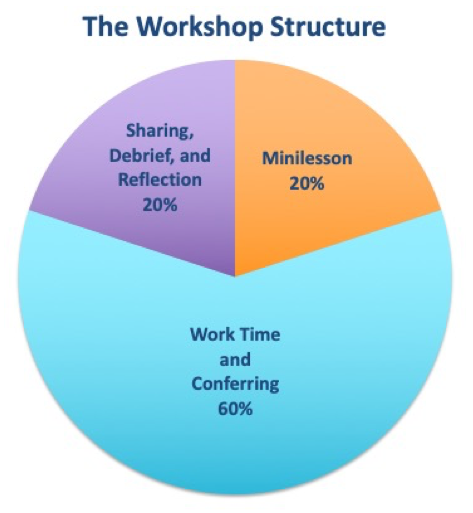

The teacher provides a mini-lesson, focused on a targeted teaching point — a single skill, strategy, or technique she knows will be helpful to students based on her observations (formative assessment) of what they are struggling with or what they are ready to learn next. The teacher thinks aloud during the mini-lesson so students can hear how she makes connections to prior knowledge, makes decisions about what to do, and so on.

The mini-lesson is followed by an invitation to students to try the strategy or technique in their own work. And the majority of the class time is allocated to students working on their own projects with the teacher stopping by to coach and confer with each of them during work time.

The workshop model creates a bridge from direct instruction to collaborative and independent practice by gradually releasing responsibility. This approach, based on the work of Lev Vygotsky, begins with the teacher modeling, then inviting students to participate collaboratively and take over the parts they can do, until students are ready to appropriate the new strategy and apply it on their own.

There are several useful models for explaining the gradual release of responsibility; the explanation I’ve found that resonates most strongly with students is: “I do, you watch; I do, you help; You do together, I help; You do alone, I watch and assist as needed” (Jeff Wilhelm, Strategic Reading). I also like to point out how popular TV shows like Worst Cooks in America, What Not to Wear, Dog Whisperer, and Dancing with the Stars use the gradual release teaching approach, too!

The workshop model and the gradual release of responsibility connect well to Gold Standard PBL.

They are ideal approaches for incorporating several of the Project Design Elements and Project Based Teaching Practices, most notably Reflection, Critique & Revision, Engage & Coach, Scaffolding, and Assessing Student Learning.

The mini-lesson establishes a clear focus and goals for student work time. Work time is prioritized. This gives students the time and space they need to meet those goals. It enables teachers to coach students, provide differentiated scaffolding, and give the timely and specific feedback needed to support critique and revision. Structured work time also provides teachers the critical opportunity to make the formative assessment observations that will inform their instructional decisions about the next day’s mini-lesson. The closure creates an opportunity for student reflection and self-assessment.

One of the ongoing challenges of being a PBL teacher is finding and maintaining balance: balance between teacher direction and student choice, between learning targets and student-driven inquiry, between high expectations and appropriate levels of support. When I’m struggling with these tensions, I find that the workshop model and the gradual release of responsibility are the frameworks I can always count on to re-center myself in my role of lead learner and PBL facilitator.

For more on using the workshop model in your PBL classroom, see “Putting PBL into Practice: The Workshop Model” by Maddie Shepard.

For additional ideas about integrating the gradual release of responsibility into your PBL practice, see “Scaffolding the PBL Shift” by Mike Kaechele.