Most teachers would like to design good projects for their students, right? But how easy is that, for many teachers? And what about the challenge of implementing it successfully?

For more than 30 years, PBLWorks focused its work on helping teachers design high-quality Project Based Learning experiences for their students. Drawing from research, we published books and blog posts, developed highly-praised workshops, created online tools and teacher support resources, and coached school leaders in building the conditions for effective PBL design and implementation.

We provided all this to hundreds of thousands of K-12 teachers all across the United States (and internationally), and yet… We still feel like we are a ways away from achieving our vision of providing all students with the engaging, powerful learning that we know PBL provides. At our current participation rate in our face-to-face professional services, it would take 295 years to reach all of the nearly 4 million teachers and their 50 million students in the U.S.!

Why PBL Doesn’t “Take” in Enough Classrooms

After attending our inspiring, multi-day, expertly designed and facilitated workshops, followed up by on-site coaching from our wonderful National Faculty, many teachers do head back to their classrooms and successfully facilitate high-quality projects with their students. In some schools, PBL takes off and teachers become proficient and enthusiastic about its use. In other schools, some teachers design good projects, but fewer actually implement them. And in too many schools, well, crickets… So what is happening?

After an initial burst of excitement, the reality of schooling often sets in. There isn't enough time to design projects; teachers don’t have enough support or opportunities to collaborate; the school schedule and culture doesn't change; and standardized tests rule the day, with the resultant emphasis on “covering content” instead of conducting in-depth inquiry. Competing initiatives lead to overloaded plates. Teacher and administrator turnover results in a loss of energy, expertise, and leadership’s focus on PBL.

And sometimes, the projects teachers design don’t work as well as they hoped. The projects aren’t engaging enough for students, or conversely are fun but not rigorous. They wind up taking too long and the logistics seem too demanding. Becoming a PBL teacher can prove to be more challenging than expected; it seems like too big of a leap from traditional, familiar practices, and takes time to master.

The Solution: Provide a PBL Curriculum, with the Right Support

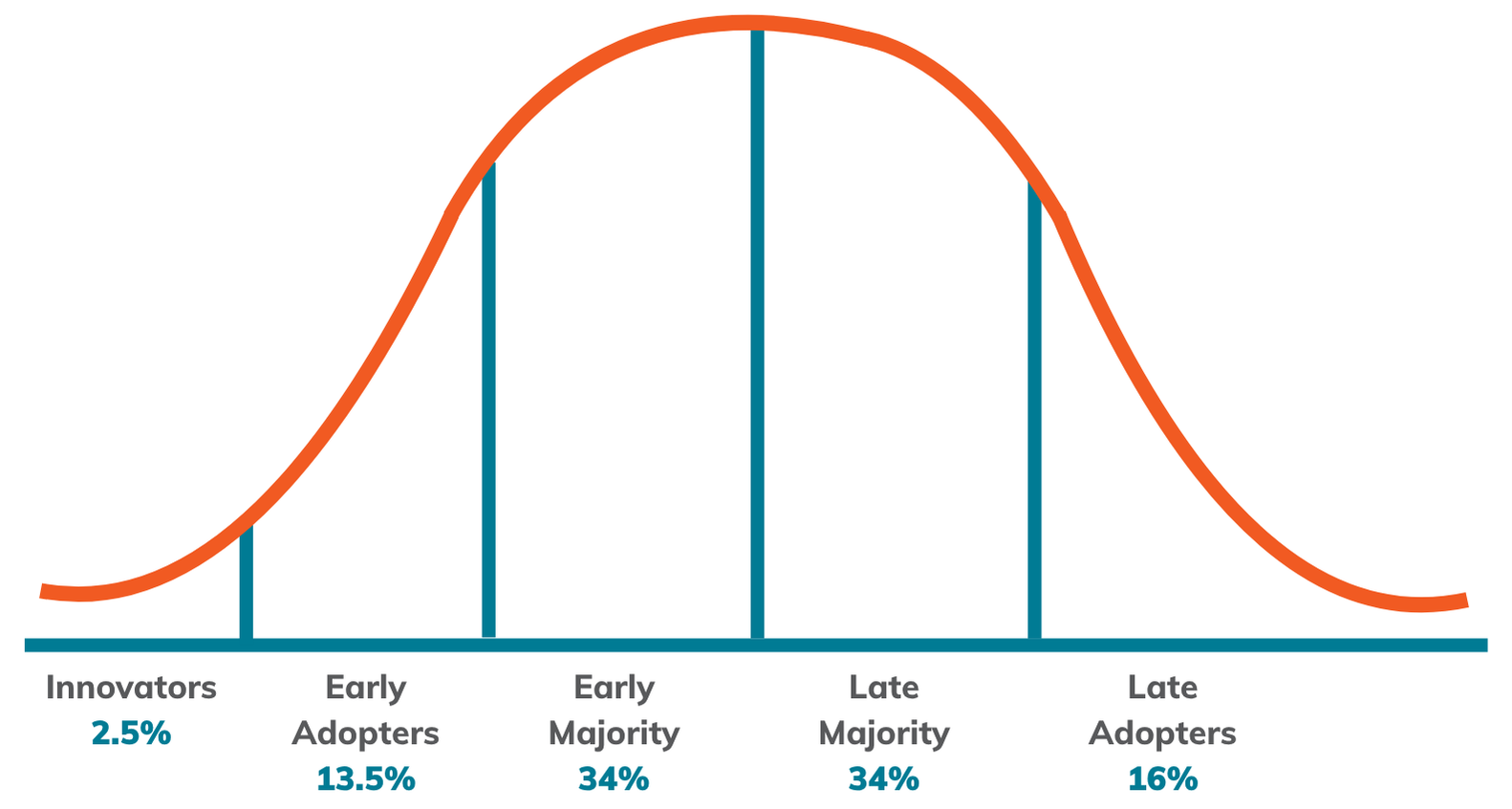

Some teachers will always want to design their own projects, and have the capacity – so more power to them. They’re the “early adopters” on the left side of the “innovation diffusion curve” shown below. But to make sure most students experience high-quality PBL, we need to reach the teachers in the early and late majority. The best way to reach them, we’ve decided, is to provide pre-designed project-based curriculum units. We’ve maintained a robust project library on our website for several years now, and now we’re moving to the next level.

PBLWorks has been developing new curriculum units for the past couple of years, and we’re about to launch them. As someone who has seen a LOT of projects over the years, I can say that these are very impressive units. To ensure quality, we’re beginning with a limited set of units per grade level – we’re launching the middle school projects first, followed by elementary and high school projects in January 2026. I’ll explain more about what’s contained in the units and how they were developed, but first let's look at some examples.

| Middle School Math |

Pack Perfection

Students take on the challenge of designing a custom backpack for a real client. They gather insights through interviews and market research, then apply their understanding of area and volume to create an efficient, personalized design. By exploring spatial reasoning strategies like “cubifying” and slicing, students make purposeful choices around storage capacity, size, and style—then present their final portfolio to the client.

Be Your Own Boss

Students launch their own startups to address community needs. After forming teams around shared interests, each student develops a unique business idea within their industry. They apply linear functions to model expenses, revenue, and profits, and use this data to build a strong business proposal. The project culminates in a Shark Tank–style pitch to family, friends, or community investors.

| Middle School Science |

Cool Communities

Students investigate the science of extreme heat by exploring how climate, humidity, and urban design contribute to rising temperatures. Through research, simulations, and field investigations, they identify urban heat islands in their community and analyze the risks they pose. Working in teams, students design innovative, science-based solutions to make these areas cooler and safer. The project culminates in a public presentation of their heat mitigation proposals to local officials and community members—blending science, design thinking, and civic action for real-world impact.

Families and Fermentation

Students explore the ancient science of preserving food through fermentation. Working in teams, they investigate lacto-fermentation at the molecular level—examining how beneficial bacteria convert sugars into acids and give fermented foods their distinct taste. Along the way, students collect and analyze data on the chemical reactions involved. Individually, they develop a fermented recipe, and as a team, they create a guide to safe fermentation. The project culminates in a community Fermented Food Fair, where students share their recipes, science insights, and cultural connections with family and community members.

| Middle School English Language Arts |

Beyond the Hype

Students step into the role of advertising professionals as they explore what makes marketing ethical in today’s media-rich world. They examine psychological tactics, consumer behavior, and real-world ad campaigns to define their own vision for ethical advertising. As agency teams, students design a multimodal campaign for a specific client, guided by their strategic vision. The project culminates in a pitch session where teams present their campaigns to a panel for feedback on impact and ethics.

Belonging

Students explore what it means to feel included—or excluded—by analyzing personal narratives in texts, videos, and audio stories. Inspired by Tonika Lewis Johnson’s Belonging Project, they examine how storytelling can challenge exclusion and create space for connection. Students write a narrative script based on their own experience or someone else’s, then collaborate to produce a short audio or video documentary. The project culminates in a public gallery where students share their documentaries and reflect on how we define and express belonging.

| Middle School Social Studies |

Rethinking the Revolution

Students explore diverse perspectives on the American Revolution using primary and secondary sources. They examine why individuals and groups supported or opposed independence—and how those choices affected their lives. Students debate these viewpoints in a Socratic Showdown and create social media campaigns that amplify voices often left out of history, rethinking 1776 to uncover the complexity of the past and how it's remembered today.

The Value of Water

Students explore how water shaped the rise and culture of four ancient civilizations. Through case studies, art analysis, and discussion, they examine how societies managed resources, faced environmental challenges, and expressed cultural values. Students create collages highlighting one civilization’s traits and work in teams to design an Annotated Map showing how that civilization adapted to and impacted its environment. The project culminates in a public art exhibit that invites viewers to reflect on water’s lasting role in human history.

Sounds good, yes? We’re aiming for a high level of student engagement along with rigorous learning, with a variety of product types and public audiences.

What’s In the Units

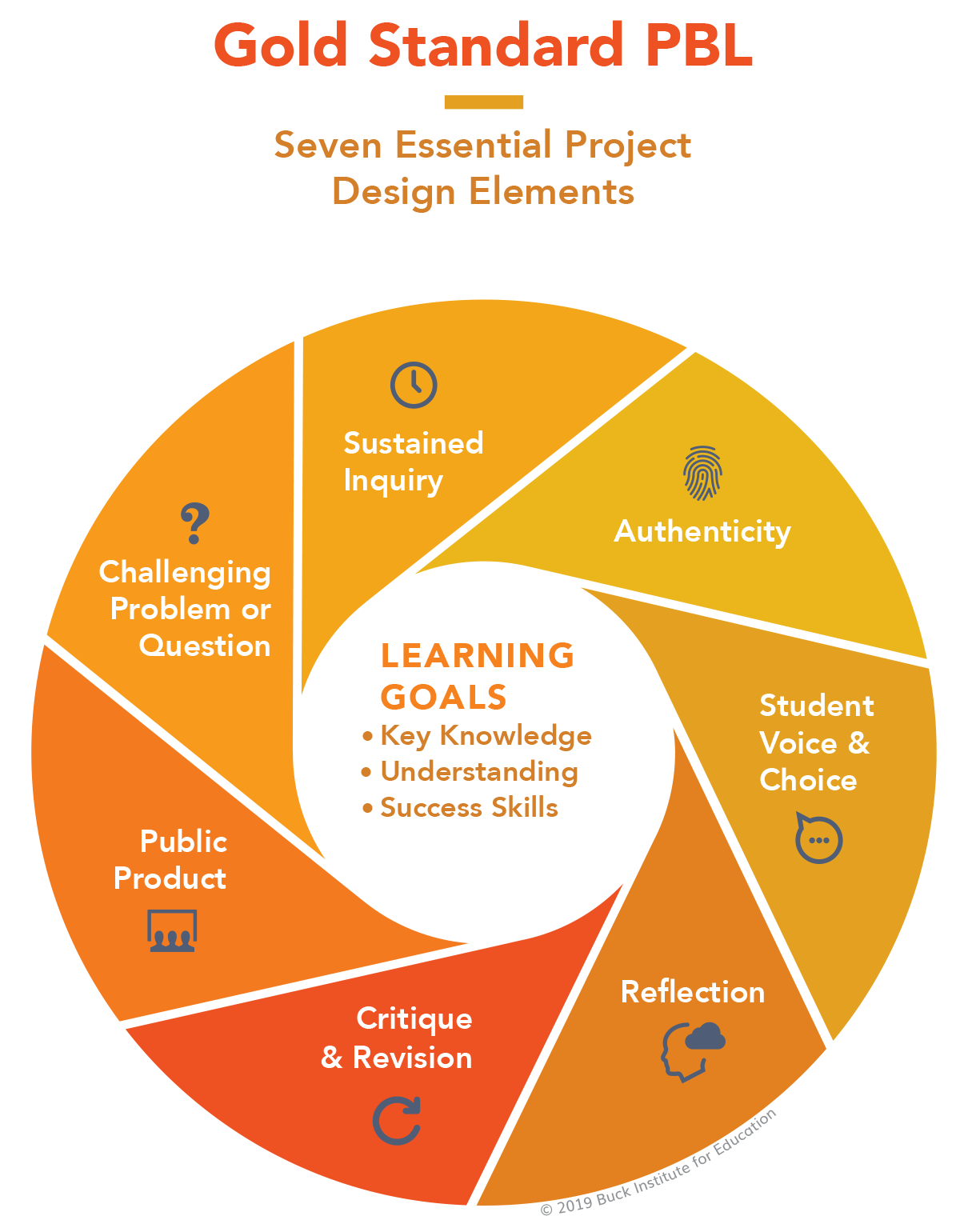

The project-based units we are creating are aligned with our model for Gold Standard PBL. They reflect all seven of the Essential Project Design Elements and Project Based Teaching Practices. The lessons within them draw upon equity-based teaching practices and culturally responsive pedagogy, and incorporate best instructional practices. Many follow the workshop model to promote student independence.

The project-based units we are creating are aligned with our model for Gold Standard PBL. They reflect all seven of the Essential Project Design Elements and Project Based Teaching Practices. The lessons within them draw upon equity-based teaching practices and culturally responsive pedagogy, and incorporate best instructional practices. Many follow the workshop model to promote student independence.

The units are impressively comprehensive. They contain everything a teacher needs to implement them successfully. Features include:

- The project’s driving question, entry event, major products (individual and team-created), and the public audience with whom students share their work.

- The content standards and success skills students will learn and practice. The projects are aligned with national standards such as NGSS, the C3 Framework for Social Studies, and Common Core Math and ELA.

- Assessment rubrics for major products plus criteria for assessing student learning in a range of smaller assignments, aka deliverables.

- Step-by-step lessons for each day of the project, which range from 18-22 class periods long, with scaffolding and differentiation strategies.

- Student handouts, readings from both primary and secondary sources, and links to videos and online resources.

I could go on, but let me just add that I really like the tips and strategies provided to teachers who may be new to PBL: How to group students in teams and build the right classroom culture for collaboration; how to conduct various types of critique protocols and use peer feedback; how to engage and coach students throughout the project; and the many opportunities for structured student reflection. To help ensure high-quality products, the units contain exemplars, frequent formative assessment, and structured work time for students. Teachers are also given suggestions and scaffolding for involving guest experts and connecting students with the world beyond school.

How the Units Are Developed

The team that develops the curriculum, led by Kathleen Schwille, follows a thoughtful process to ensure high quality. The math and science units are overseen by Telannia Norfar, a former longtime PBLWorks National Faculty member. Dr. Ari Dolid leads the work in English and Social Studies. Working with them are unit developers with content-area and PBL expertise, and writers with extensive experience in curriculum development.

The process begins with a survey of national and state standards to determine the topics, knowledge and skills the units will focus on. The goal is to make sure the units will appeal to a large number of teachers and students across the country. We know that for PBL to become widely used, teachers need to be assured that the time it takes to conduct a project will pay off in terms of student learning, and they can still teach important standards. As Ari puts it:

“We are designing the units to easily replace existing units that teachers already teach. We identify standards, topics, themes, and units that teachers already are responsible for teaching, and are providing an alternate way of teaching those important things.”

Or as I once put it, these are not “dessert” projects, they’re “main course” PBL!

From there, we have a rigorous quality-assurance process. At each step of the way, PBLWorks staff review the units and provide feedback–we engage in critique & revision just like we ask students to do. First, developers and writers create a “project concept” that paints the big picture - the content/topic, a summary of what students will do, the driving question and major products. A “unit build” comes next, with more details to guide the writers, which is also reviewed for approval. Then the complete unit is written, which is field-tested by teachers and fine-tuned. This is followed by another review, after which final revisions are made and it goes into production.

Launching June 1! PBLWorks TEACH™

This is exciting: the curriculum units will be made available on a new app we have developed: TEACH. Teachers can access all the features of the units on the app, as well as links to professional learning resources for just-in-time support. For example, a teacher can watch a short video about a particular critique protocol, or learn more about managing end-of-project presentations to a public audience.

The theme of this year’s PBLWorld gathering is “hope.” In that spirit, I hope our new project-based curriculum units help many, many teachers and students reap the benefits I know PBL provides!