As an educator and library media specialist who values best teaching practices, I have always been aware that allowing student voice in the classroom leads to more authentic learning.

I give students a menu of options for summative assessments to evaluate learning, facilitate student co-construction of rubrics and give them free range for independent reading choices. This year, I undertook my first school-wide research project during library in conjunction with our work with the Students Rebuild Hunger Challenge. To my surprise, my students’ persistent voices put a kink into my well-laid plans.

I attended PBL World last summer. After getting feedback from colleagues and a member of the PBLWorks National Faculty, Myla Lee, I left with my project planner complete. I began the 2019-20 school year with confidence that my research project would have all the components of a fantastic Project Based Learning experience. My administrator would be impressed, my students’ parents would be thrilled, and my students’ engagement would have never been higher.

I patted myself on the back, since my students would be both learning and engaging in civic responsibility, and believed nothing could be more interesting to them than deeply considering our driving question.

Enter my students, from kindergarten through fifth grade, who are not afraid to exercise their student voice and make sure their ideas are heard, loud and clear.

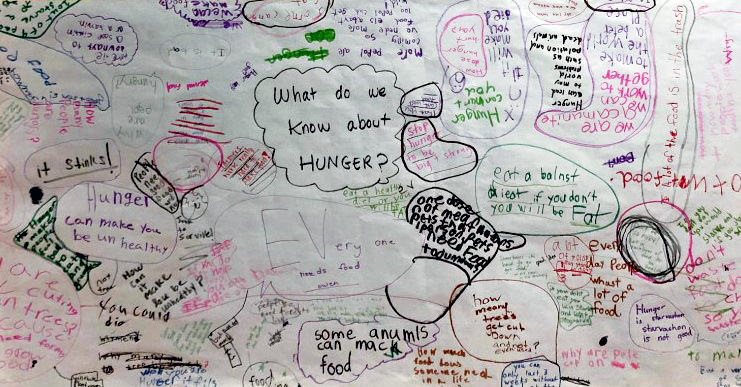

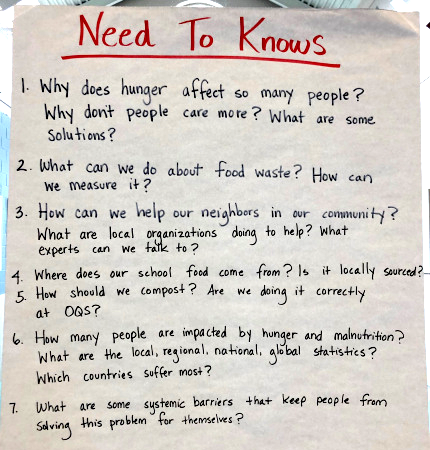

We began our work with a whole school “chalk talk” outlining what we already know about hunger and malnutrition, with students building off each other’s ideas and making connections between their grades. The next step in my plan was for students to generate the “need to know” questions that would guide our research, which I undoubtedly believed would align perfectly with my detailed and rich unit plans. I was confident I knew exactly where my students were heading.

It quickly became apparent, however, that what I thought would be the focus of our research (creating a scientific field journal of healthy, local foods that we could share with local restaurants and families about the benefits of eating well) was a complete non-starter. The students loved the idea of working with local restaurants and inviting chefs to collaborate on healthy menu items. But they were not at all interested in doing a deep dive into which healthy foods we can grow here in Vermont.

What my students care passionately about is social justice, advocacy and community outreach. And what they actually wanted to focus their research on was learning about how people are impacted by hunger in our community—and what we are going to do about it. At that moment I was surprised, but after reflecting on my students and how empathetic and motivated they are, I can’t believe I did not think of this direction myself.

As I jotted down all the things my students brainstormed they needed to know: Why does hunger affect so many people? What can we do about wasting food? What are some barriers that keep people from solving this problem for themselves? I was faced with a real-time teacher dilemma. If I took my students’ words to heart and let them drive their own learning—which I knew was what their voices were telling me—I would have to disregard hours of my own work backward mapping a unit that was now defunct.

I would have to put more hours into my already busy planning schedule to figure out where this unit was even going.

What community partners would I need to reach out to? What are the learning targets? What are the formative and summative assessments? It was tempting to nudge them back to the track of least resistance, the track I had so carefully laid out for them over the summer without their voice or choice. The one that would be easier for me.

I knew in my educator heart that I couldn’t do it. The skills I wanted my students to master were still embedded in the learning; we were just taking a different approach to arrive at the same goals. I wouldn’t have to lay waste to all my planning; I just needed to join forces with my students to figure out what milestones were needed for them to be successful in both their mission to help our community and my mission to teach them research skills. In conversation with two of my fourth graders, they reflected things like, “people are counting on each other to help,” and “we need to come together to make sure everyone has enough.”

After observing their passionate demands and how they would not rest until they found answers, I knew we couldn’t go back to scientific field journals. I had given them a platform to amplify their voices. Now it was my job to listen.

Student ideation and collaboration teaches skills beyond learning targets and basic objectives.

Deep, authentic learning that engenders growth comes from educators’ willingness to do the hard work. And that means it’s time we walk beside our students instead of in front of them leading the way.