Many times when I use rubrics in my PBL practice, I use the term “able to teach” as the highest indicator of proficiency. The ability to communicate content to others is a step above the ability to simply understand content ourselves.

However, it occurs to me that if we evaluate students on their ability to communicate a high level of knowledge, why not let them in on the strategies that we use to do so ourselves? This takes calling out our own strategies and cracking open our toolbox to let students look inside. It means letting them see how we coach, set goals, build classroom culture, and assess.

In PBL, teachers share with students some of the duties done solely by teachers in traditional classrooms. We want students to learn:

- How to give feedback to each other, with sensitivity and specifics

- How to help answer each other’s questions with accuracy and willingness

- How to agree on norms with their small groups by being proactive about possible conflicts, making compromises, and reaching consensus

- How to set goals and track their progress by looking clearly at the evidence that supports their growth

We’re asking them, in a sense, to think through an educator’s lens—but it takes training. It requires developing intentional lessons that help students understand more deeply the Project Based Teaching Practices that go into giving feedback, finding answers, setting norms, setting goals, tracking progress, etc. It means ensuring that learning these practices is integrated into the actual lesson, not just working invisibly behind the scenes.

How Students Can Use 4 Project Based Teaching Practices

1. Align to Standards: Students can look at the standards just as easily as teachers can. Introduce your students to your state and district goals, and vision and mission statements. Call them out as intentional objectives. Help students identify the 21st century success skills like collaboration and communication. Much like many teachers do, have students reflect on and predict which ones might prove most challenging. Help them set personal goals and use evidence to prove the goals have been met. During one PBL unit I observed in a middle school special education class, students stood beside their culminating product, one based loosely on the video of Caine’s Arcade. The students had designed games for younger students to play to help teach a science or history standard. They also talked to the theme park attendees, standing next to their game and holding iPads that included a three-slide Google Presentation that included the following:

- Title slide with name and IEP goal

- Science or history standard they chose to focus on meeting

- Evidence (2-3 sentences) that proved the standard had been met

2. Build the Culture: When we have students collaborate, we are often asking them to quickly build a culture with their small group. Point out the strategies you have used to build the classroom culture. Maybe it’s using “attendance questions” or ice breakers. Maybe it’s developing a classroom constitution of some kind. Give students time to build the culture within their smaller cohort, especially if you, as the teacher, have decided who’s in the group. When my students develop collaboration contracts for our PBL units, they develop the following:

- Norms stating decided-upon roles

- Conflicts they anticipate might arise

- Steps to resolve conflicts (before going to the teacher for mediation)

- Mission statements focused on the purpose of the work

- Methods of communication and the length of time before not responding is considered unacceptable

Students also design ways to report back on daily individual work, and they even create and engage in an ice breaker or two.

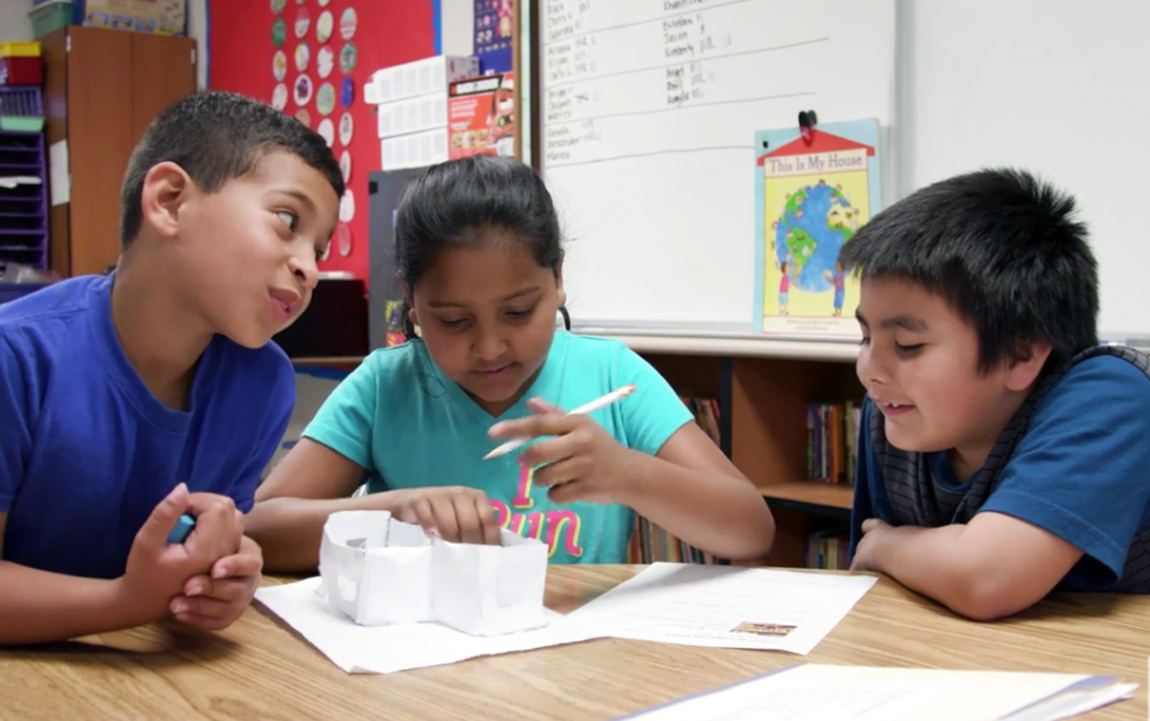

3. Engage and Coach: Students can learn to share the responsibility of encouraging and advising their peers. Teach students to critique each other by using the tricks of a great coach.

- Give students an opportunity to contribute to sustained inquiry by asking questions to gently advise peers to push themselves and their work.

- Have students engage in protocols, like the charrette, that intentionally promote listening through structured silence as part of how we interact with each other.

- Encourage students to utilize jigsaw activities that allow each student to become an expert in a particular piece of reading and share out their expertise to the group.

4. Assess Student Learning: Students can learn to assess each other as well as themselves. They can help develop criteria for success and fill out rubrics for peers or for themselves. They can translate teacher-created rubrics into ones with more student-friendly language. They can look at an exemplar and develop the criteria that describe “exceeds” and “proficient.” They can also be a part of the evaluation process as a means for feedback. One school I worked with asked students to develop portfolios and have them assessed four times throughout the school year using the same rubric:

- In the first quarter, it was assessed by the teacher.

- The second assessment was done by another staff member on the campus, from groundskeeper to principal.

- The third assessment, however, was conducted by a peer.

- The final assessment was assessed by the student who created the portfolio itself.

Make your teaching strategies transparent by sharing your toolbox with your students. Draw back the curtain on what we do to create the conditions that enable us to help them learn more deeply. Your students will grow from interacting with the process— and get closer to attaining that “able to teach” level!